Soaking It In: The Chemo Sponge

/The myriad adverse effects of chemotherapy are the stuff of modern legend. The nausea, vomiting, anemia, fatigue, hair loss and other side effects of the drugs designed to either cure or reduce cancer can sometimes seem worse than the cancer itself.

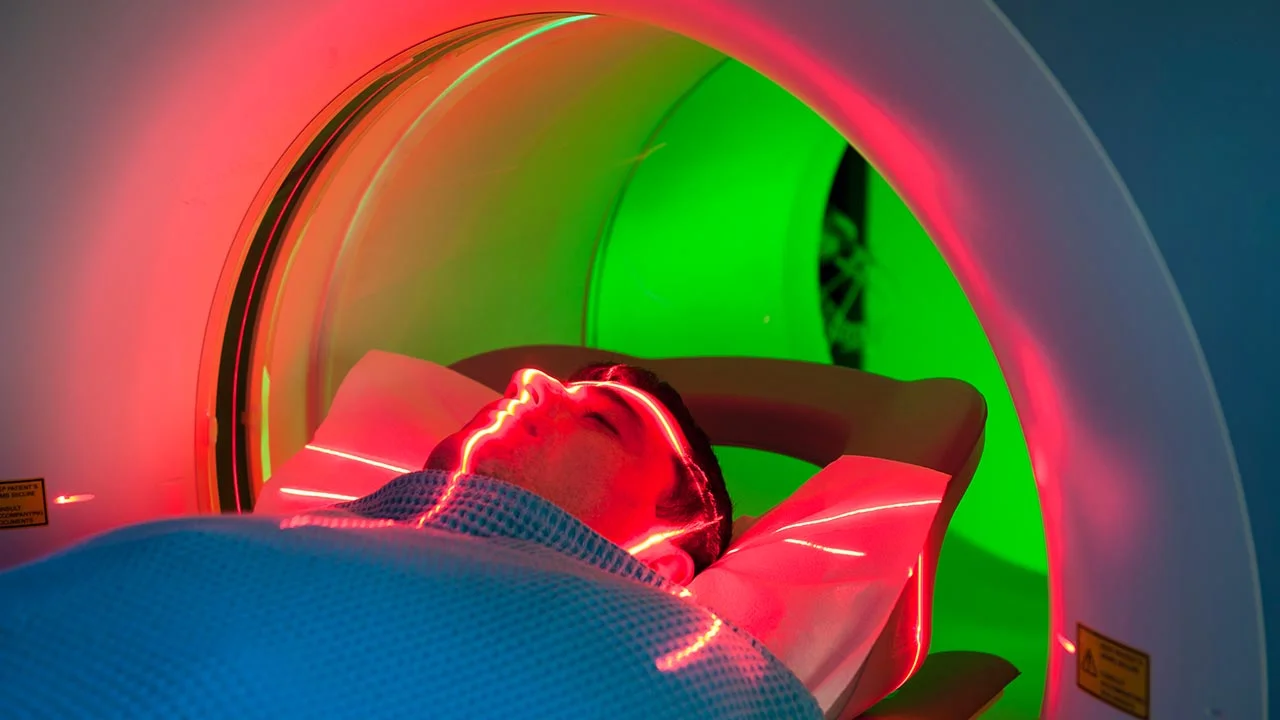

One approach to stave off the suffering has taken the form of targeted delivery of the drugs through nanotechnology. Now, researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) are looking at a new approach. They are developing and testing materials for a device that can be inserted via a tiny tube into a vein and soak up most of these drugs like a sponge. That’s after a separate tube delivers a more concentrated dose to tumors — and before the drugs can widely circulate in the bloodstream.

Researchers say the drug-capture system could also potentially be applied to antibiotic treatments in combating dangerous bacterial infections while limiting their side effects.

X. Chelsea Chen, a postdoctoral researcher working in the Soft Matter Electron Microscopy program in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division, had been investigating polymer membranes — which help current to flow in a fuel cell that converts hydrogen and oxygen into electricity — when she learned about the concept for this new type of medical device.

She saw that the proposed drug-capture device could benefit from the same property in the fuel cell material, which allows it to attract and capture certain molecules by their electric charge while allowing other types of molecules to flow through.

“We used to use this material for transporting protons in a fuel cell,” Chen said. “I was really excited when I found out this could be used for chemotherapy — this was branching out in a totally different direction.”

The polymer material includes polyethylene, which is strong and flexible and is used for garbage bags, and another polymer containing sulfonic acid, which has a negative electric charge.

Certain types of chemotherapy drugs, such as doxorubicin, which is used to treat liver cancer, have a positive charge, so the polymer material attracts and binds the drug molecules. “In our lab experiments, the current design can absorb 90 percent of the drug in 25 to 30 minutes,” Chen said.

That is important, since an increasingly popular liver-cancer treatment, known as TACE, can allow up to half of the chemotherapy dose to reach the rest of the body even though it is intended to reduce its circulation.

The research team received a patent for a ChemoFilter system in April. The patented device features a nickel-titanium metal frame in a collapsible flower-petal array, attached to a thin polymer membrane that can be expanded out from a catheter to absorb a drug. In a preclinical study, a ChemoFilter device was inserted into a pig and was found to reduce the peak concentration of the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin by about 85 percent.

Chen and other researchers are also working on next-generation ChemoFilter devices that use a different mix of materials and different methods to remove drugs from the body.

The membranes could also be designed to capture antibiotics to treat potentially deadly infections from anthrax and other bacteria.