The Hidden Sugar in “Healthy” Drinks

/Most parents have their guard up against fizzy soft drinks. They know full well that dangers of sugar, and so try to steer their children toward healthier beverages such as fruit juice or fruit smoothies. And that's what makes the data from a new study at the University of Liverpool and the University of London in the UK, so insidious.

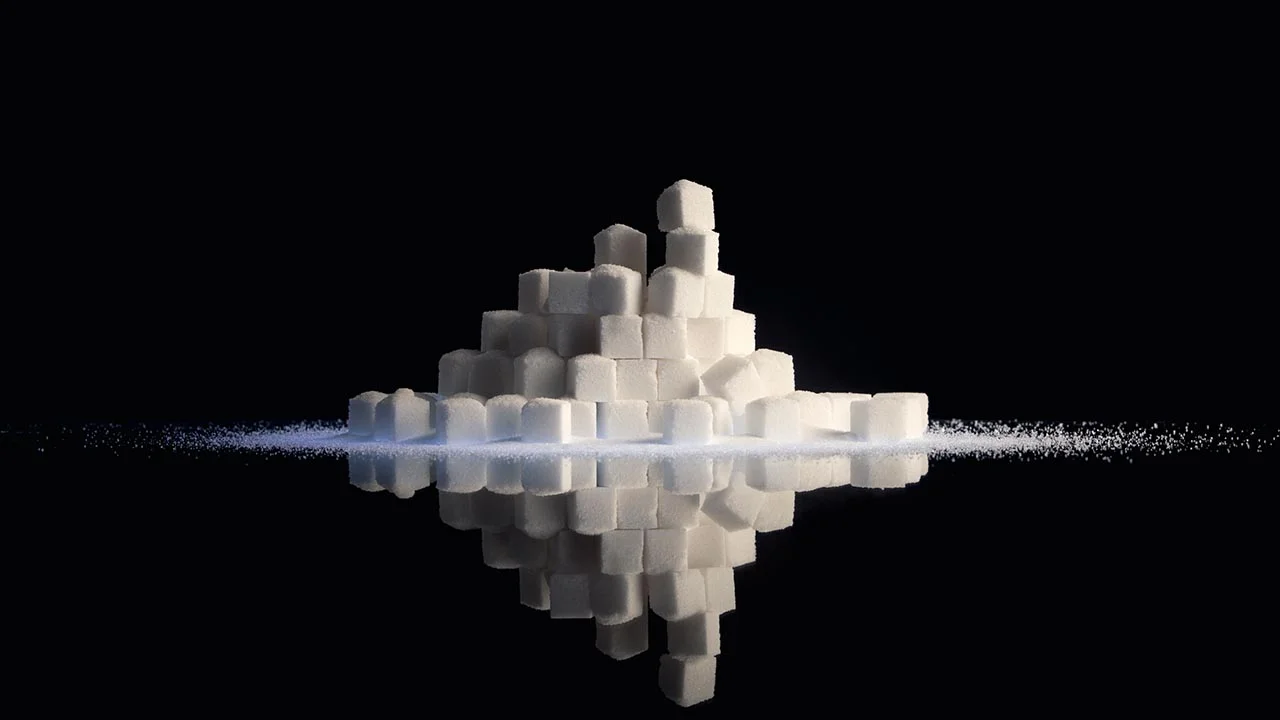

According to the research published in the journal BMJ Open, the sugar content of fruit drinks, natural juices and smoothies, in particular, is "unacceptably high." Specifically, the researchers discovered that almost half the sampling of 203 drinks, purchased at local supermarkets, contained a child’s entire recommended daily intake of sugar, which is a maximum of 19 grams or nearly five teaspoons. One 12-ounce can of soda contains 10 teaspoons of sugar. The American Heart Association recommends no more than 3 to 4 teaspoons of sugar a day for children, and 5 teaspoons for teens.

The scientists checked the amount of "free" sugars in 203 standard portion sizes (about 7 ounces) of UK-branded and store-brand fruit juice products. Free sugars include glucose, fructose, sucrose and table sugar, which are added by the manufacturer, as well as naturally occurring sugars in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. Although fructose occurs naturally in fruit, when consumed as a drink, it can cause dental cavities, as can any other sugar.

The researchers had some recommendations, for consumers and bottlers:

· Eat fruit whole, not as juice;

· Limit intake to just over 5 ounces per day;

· Dilute fruit juice with water or just drink unsweetened juices, and allow these only during meals;

· Require manufacturers to stop adding unnecessary sugars to fruit drinks, juices and smoothies.

They are also of the opinion that fruit juices should not even be counted as part of a child's daily recommended daily fruit consumption. In addition to containing a much higher fiber quotient than juice, whole fruit takes longer to consume, is more satisfying, and there is evidence that the body metabolizes whole fruit in a different way, adjusting its energy intake more appropriately than it does after drinking juice.